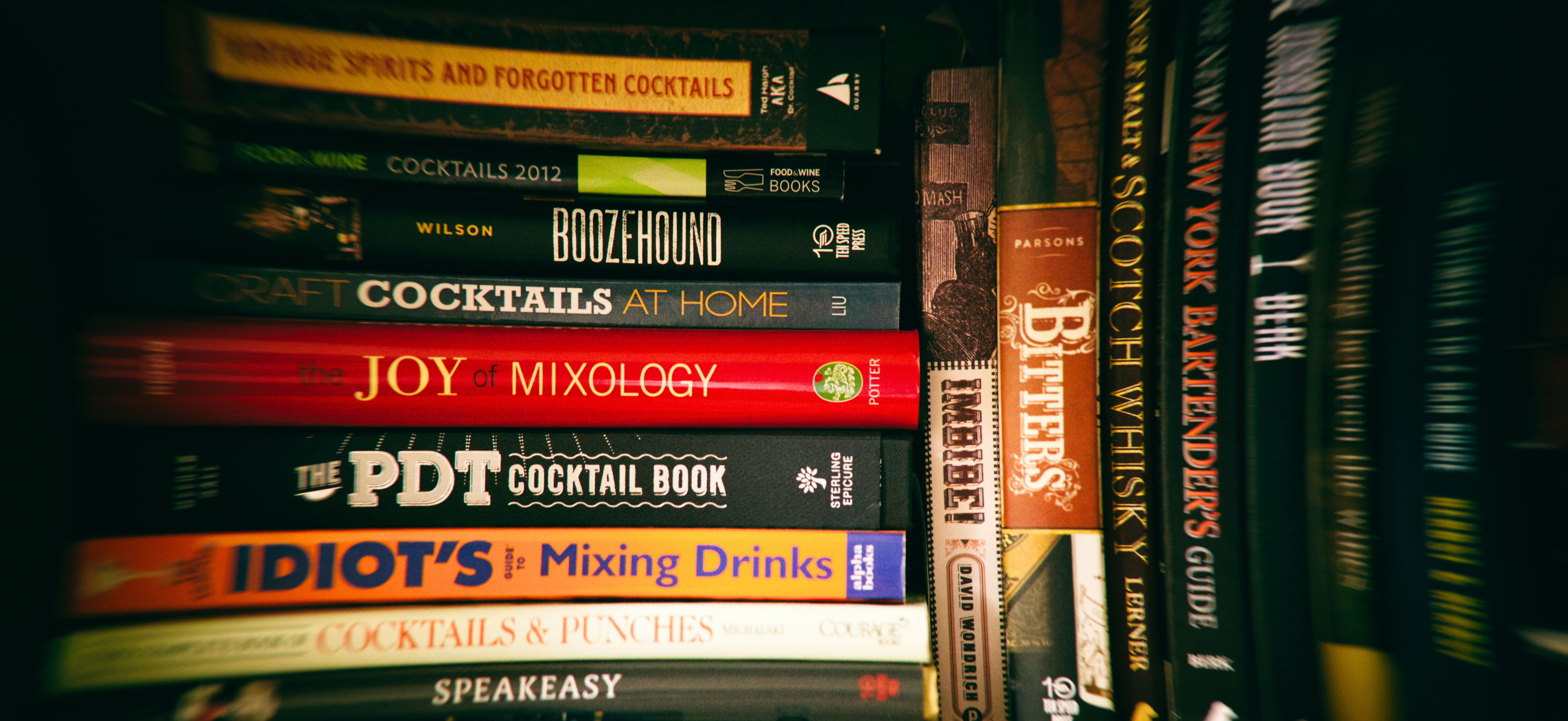

With a few additions, the essential cocktail gear is transformed into a well-equipped set. Novel or situational utility can found with further acquisitions, but most such items lack any sort of universal applicability.

Well-Equipped Additions to the Bare Minimum

Waiter’s Corkscrew

We need to start by dealing with some awkward truths. If making cocktails, one will be called upon to open wine. That is not all, however. Sometimes a stopper breaks, leaving a cork in the neck of a bottle. Some exotic, rare, or irritating bottles of liquor also come with cork closures.

A waiter’s corkscrew is the best tool for the job. It is compact. It can open all but the trickiest vintage wines. It can open a bottle of beer in a pinch.

The best waiter’s corkscrew is the Code38 Wine Knife. By price alone, this item belongs on the “nice to have list” instead.

The $25 Screwpull Waiter’s Corkscrew is an order of magnitude less expensive and still quite capable. The dual-action lever is forgiving of inexpert technique (those with more experience will prefer a single-action knife).

Bottle Opener

Same story with the bottle opener. Beer will happen. While a lighter or a waiter’s corkscrew works in a pinch, they don’t work well. There are, however, other reasons. A lot of things that get mixed into cocktails come in glass bottles with caps: Ginger beer, tonic water, etc.

The correct tool for the job is the Pro Cap Opener. It is just a stamped piece of stainless steel. It is indestructible. It is simple. It is dishwasher safe. It works better than any other bottle opener.

Japanese Mixing Glass

The mixing glass is necessary to properly produce stirred drinks. At first this might seem contradictory. For the cocktail shaker, I avoided the classic Boston shaker, which pairs a glass cup with a metal tin. There are several reasons for this, but two notable ones: Glass breaks and glass causes more dilution. While the first is obvious, the second is a bit more confusing. A metal mixing tin better transfers changes in temperature than glass. The intuitive result from this might be that the cold would leak out quickly. In reality, the tin quickly gets rather cold and that’s about the end of it.

Glass instead takes a significant amount of energy to chill. Where frost quickly forms on the outside of a metal tin, a mixing glass used for a solid minute may only present a slight chill to the touch. The amount of energy spent chilling the drink and the mixing vessel is directly translated to water that dilutes the drink. Pre-chilling the mixing glass minimizes dilution and a room temperature (or warmer) glass maximizes it. I could go on about how important some dilution is, but the key takeaway here is that the mixing glass provides more control for stirred drinks.

More fine-grained dilution control is not, of course, the only reason for the mixing glass. First off, the size is carefully chosen to be a good volume, radius, and depth for preparation of drinks. Second, a well-designed spout makes pouring the drink for service more straightforward than when draining from a mixing tin. Most important, however, is that the thing is heavy. It is easy to vigorously mix a drink in a mixing glass for a solid minute with one hand on the bar spoon and minimal attention to it otherwise. A shaker tin or other substitute is far more likely to be knocked over with a quick bump or without careful attention during stirring. Even the weighted Koriko tins are pretty lightweight compared to a nice chunky mixing glass.

I recommend the mixing glasses from Cocktail Kingdom, starting with the inexpensive Yarai Mixing Glass at about $33. Things go up from there to get either seamless fabrication, larger vessels, or different decorations. The Yarai pattern provides an easy grip when the glass is cold and wet; it’s not just for show.

With that said, a decent stand-in (and multitasker) for a Japanese mixing glass is a pitcher used for milk steaming in espresso drink preparation. The Rattleware 20 Ounce pitcher is a great option for about $17. It has some weight, is relatively squat, and has a handle to help stabilize the process.

Julep Strainer

Stirred drinks must be strained. Nothing prohibits use of a Hawthorne strainer with a mixing glass. A Hawthorne strainer does a great job catching small ice chunks while still permitting liquid to flow well around the rim of the strainer. It also excels at sitting atop a mixing tin, rather than inside of it. Both of these qualities are detrimental to use with a mixing glass, in which we want to take advantage of that lovely spout.

The Julep strainer is great for straining stirred drinks because it sits inside a mixing glass. This allows the liquid to flow through the spout. Unfortunately, the Julep strainer cannot be The One True Strainer because it jams up quickly with small chunks of ice and does not fit particularly well in a mixing tin.

If one can only have one strainer, it should be a Hawthorne, but a well-equipped bar needs a Julep strainer, too. I like Cocktail Kingdom’s Julep Strainer for $11.

Muddler

Several cocktails require muddling. A few bar spoons can do a passable job of this in a pinch, but the best tool is a muddler. A muddler should have some heft and be sturdy: they are not tools that grow old through gentle use. One very important detail is that a muddler should be a single piece. A muddler that is screwed, glued, or otherwise fused together will fail or grow nasty things. The world is full of muddlers with metal handles or bodies joined to plastic handles or tips. They. All. Fail.

I still struggle deciding between flat and corrugated heads, but my current go-to muddler is a $6 polycarbonate model. It’s food-safe, dishwasher-safe, and tough as hell.

Cigarette Lighter

Like beer and wine, lighting a cigarette may become necessary at times. Candles must burn! That is not why we are here, however. As covered in my Negroni tutorial, fire is necessary in order to flame a citrus peel. A cheap Bic lighter works fine. Using a nice lighter is a bad idea for a very important reason: citrus oils, ignited or not, will slowly build up on the lighter. Cleaning away this residue is not fun.

The alternative is to use matches. The problem is that cocktails are big on aromas, and the smell of sulphur is not an aroma often desired in a drink. Cigar tapers get around this problem but may be more of a hassle to acquire. On the upside, a cigar taper provides a lot of relief versus a normal match or lighter. Anything that keeps the fire and oils away from the hands is a win in my book.

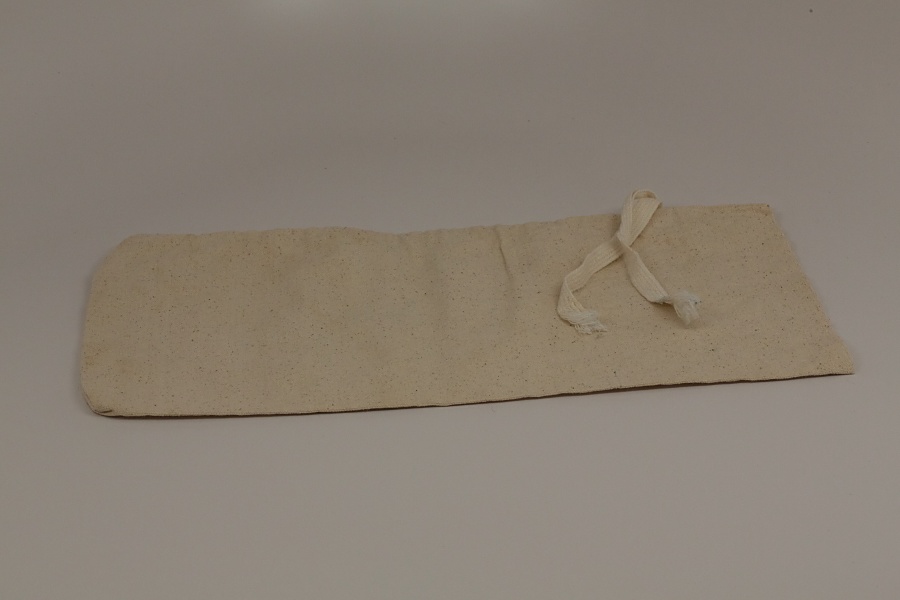

The Lewis Bag

A blender has no place in serious cocktail work. Crushed ice, however, is of some import. Transforming cube or block ice into crushed ice requires three things. The first two are ice and a Lewis bag. The Lewis Bag was designed to be tough so that it could transport coins for banks. This is good since the way we will make crushed ice is to beat the crap out of a Lewis bag filled with ice. As an added benefit, the Lewis Bag is absorbent. This keeps moisture from melting ice in the bag, instead of the drink. Cocktail Kingdom sells a quite suitable Lewis Bag for $4.

A Carpenter’s Mallet

Once the ice is inside the Lewis Bag, violence is necessary. A great way to crush the ice in the Lewis bag is to beat the crap out of it with a large woodworking mallet. I use this $20 mallet, but as long as it’s large, has some heft, and is blunt, it should be just fine. Beat ice-filled bag until desired crush size is reached. Easy and effective.