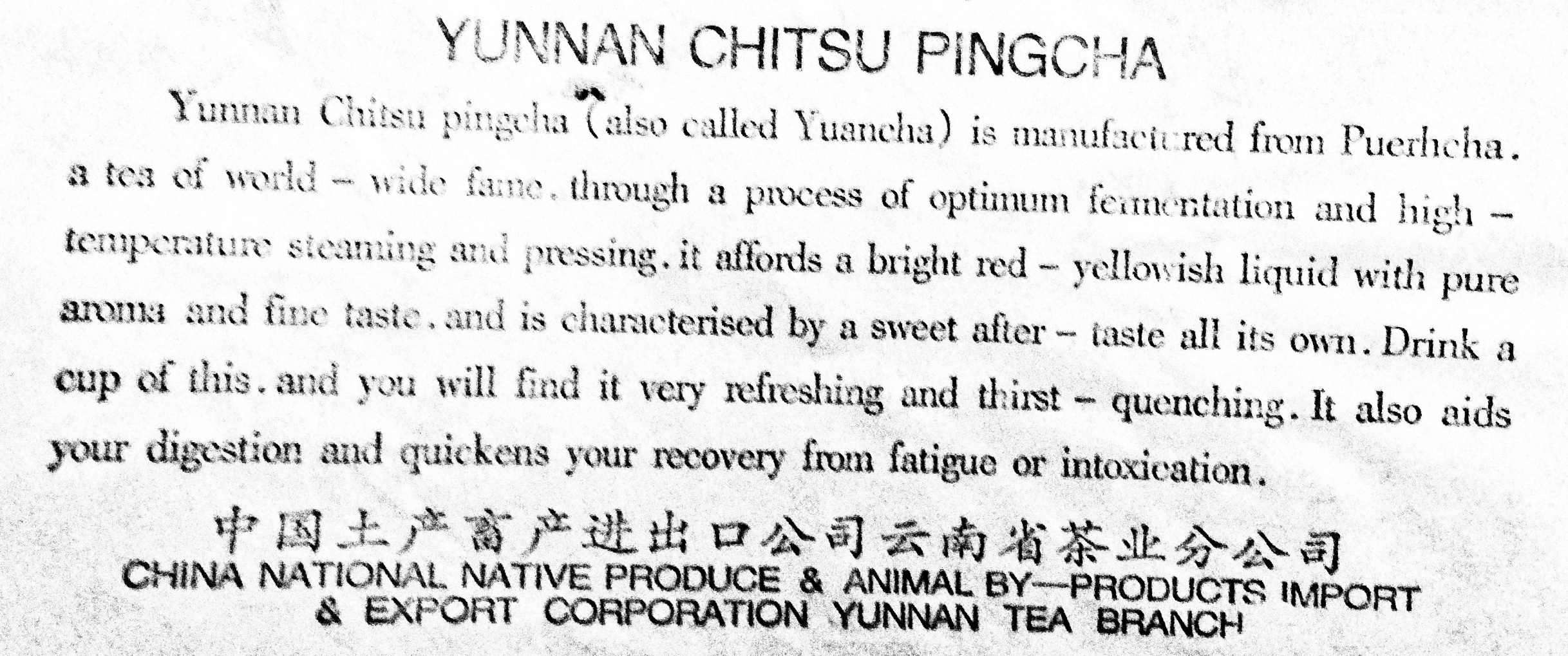

For the Western tea drinker, pu-erh is some pretty weird stuff. Pu-erh is a fermented dark tea, and finding good examples is not trivial. It is produced in China’s Yunnan province and is nothing like Yunnan tea with which many tea drinkers are familiar.

At Teavana it is found in a black tea tin, because it is blended with Yunnan black tea. This should not be taken as a representative sample. Pu-erh tea is traditionally a red tea, in fact. This should not be confused with Rooibos, marketed as red tea just to confuse things.

Here’s how pu-erh works. The tea leaves are dried and rolled. The tea is either left loose (like most tea), or can be pressed into a brick, disc, or hemisphere. Whether loose or compressed, the tea then undergoes fermentation and oxidization. This process is gradual and takes a lot of time, resulting in something somewhat unique in tea: There is such a thing as vintage pu-erh. To wit, good pu-erh improves with age not unlike good wine!

Raw Versus Ripe

It is unforunate that things are not quite as simple as I pretended.

There are two varieties of pu-erh, raw and ripe. Raw puerh is what is described above: The tea leaves are dried and pan fried briefly to arrest enzymes in the leaves (preventing immediate oxidization). They are then rolled into strands and either kept loose or compressed into a cake. In terms of color, the tea is approximately green at this stage and will likely visually straddle the green/grey spectrum. Over time, the tea will oxidize through various processes (bacteria, fungus, and autooxidation). It is best that this happens over a long period of time in optimal conditions.

Like fine wine, ideal conditions are somewhat cool and high in humidity. The tea will improve for several years, and good examples can easily improve over the course of half a century of aging. Like fine wine, young raw pu-erh is not in and of itself bad, but the tariff paid has more to do with the tea’s potential than with how it drinks upon release. It is not uncommon for a young raw pu-erh to be quite bitter, strong, astringent, and have notes similar to green teas. With age, the tea becomes more smooth and integrated, with just a hint of bitterness and none of the fresh or astringent aspects. Half a century of age should see the tea reaching its peak, with it being undrinkable around the 100-year mark.

Ripe pu-erh is a somewhat modern innovation (developed during the 1970s). Consider it the Parkerization of pu-erh. The goal is to accelerate the fermentation, approximating the effect of aging raw pu-erh for a decade or more. Thus, a ripe vintage pu-erh on release is intended to be ready for drinking. To make ripe pu-erh, the leaves are kept moist and are moved often. In essence, prodction of ripe pu-erh is not unlike controlled composting of leaves. This sounds a little gross, but then what’s happening with raw pu-erh over time is not exactly flowers and sunshine. Ripe pu-erh upon release is already darkened and produces a red liquor. Moderate additional aging may see benefit, but ripe pu-erh will not develop and improve for decades in the same fashion as raw.

In terms of flavor characteristics, ripe pu-erh on release has strong flavors and is very earthy. Where great Burgundy has notes of sous bois, ripe pu-erh can be like a heaping mouth full of decomposing leaves and dirt. The better examples are more close to the experience of aged raw pu-erh, but this really is California Cabernets versus Bordeaux. While some additional aging after production may improve a ripe pu-erh, extended aging in terms of several decades is not going to make much of a differeence.

“Making Tea With Effort”

Pu-erh is best prepared gongfu style. Gongfu preparation is heavy in ritual and ceremony. There is a lot of variation, and canonicalization is difficult at best. This is a blog about beverages and not the rituals associated with them (for the most part). As far as I am able to research, the key aspects of gongfu for pu-erh are:

- Use of a relatively high tea to water ratio (3-5 grams for 100-200 mL of water; Western custom is just over 2 grams for that quantity of water).

- Rinsing/cleaning/awakening the leaves through one or more brief steepings. This cleans the leaves, opens them up, and reduces the caffeine content.

- Use of a small teapot or gaiwan to prepare the steepings. Service into a small (or several small) tea cups.

- Repeated steepings over time, increasing in duration, appreciation of different characteristics over time.

My process is first to warm a seasoned Yixing teapot with boiling water. A service pitcher and tasting cups are also warmed with boiling water. The tea is measured and placed in an emptied (warm) teapot, and is covered with boiling water for a few seconds. This water is poured off. This step is repeated, again discarding the water. The point here is washing and opening the leaves, with the side effect (good or bad) of taking some of the most soluble compounds with it (e.g. caffeine). Production of pu-erh is far from sanitary and this is a variety of tea that features decomposition and rotting (or fermenting if we want to give it a nice name). A good washing does little to impact the flavor in the cup, but gets rid of the nasty bits and grit.

Then I make the first pot for consumption; only about 15 seconds of steeping is necessary before straining the tea pot to a service pitcher, and pouring into tea cups for tasting. Each time the service pitcher is emptied, another round is made in the tea pot, until flavor is lost or interest wanes. Five pots of tea are, in general, the bare minimum.

The alternative approach leverages a gaiwan. The gaiwan is easier to clean, does not absorb flavors (for better or worse), and has the added advantage of making it easy to stir the leaves during steeping. I find the teapot to retain warmth somewhat better and I enjoy the character the teapot develops in terms of flavor over time. Assuming I do not break it in some ham-fisted fashion (likely), this should continue to develop for years to come.

Where to Get Pu-Erh

Some “pu-erh” may be available at one’s local Whole Foods. It is probably loose pu-erh, small brick squares, or small tuocha (little hollow hemispheres). It is virtually guaranteed to be low-grade and ripe. Acquiring fine ripe or raw pu-erh requires a shop that specializes not just in tea, but in pu-erh in specific.

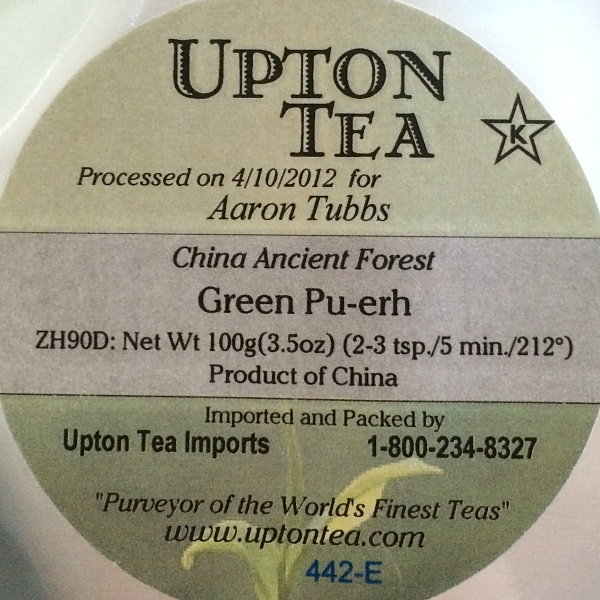

For example, my go-to tea shop for over a decade has been Upton Tea Imports. Upton is located in Hopkinton, Massachusetts, and is fantastic. Unfortunately, when it comes to pu-erh, they are not great. They have a small variety of loose pu-erh and compressed squares or mini cakes. On rare occasions they have a full compressed cake available. Primarily a mail-order operation.

I stumbled into Ku Cha in Boulder, Colorado. Their selection is quite good and provides a decent amount of variety. Staff is knowledgeable and there is ample seating in the back for those wishing to enjoy tea on the premises. In addition to the physical storefront and tea house, they do offer mail-order delivery.

I know almost nothing about PuerhShop.com beyond that they sell tea and accessories exclusively via their website and are located in Troy, Michigan. With that said, I have had great luck ordering from them thus far. They have hundreds of puerh teas including numerous vintage-designated cakes. Many are available in sample quantities. They also have a healthy collection of the equipment necessary to make tea gongfu style, including pitchers, strainers, teapots, gaiwans, knives, tool sets, towels, trays, and so forth.

Undoubtedly there are other places to acquire pu-erh, and I have only scratched the surface. Even eBay has a healthy collection of vintage pu-erh. I am warned that like fine wine, the provenance and authenticity of truly rare lots of hard to verify. If nothing else, teas older than a decade or two should only be procured from a well-trusted and reputable dealer. Hopefully anybody rushing from this article to purchase a $50,000 cake of mid-century pu-erh already realizes this.

A Tasting of Several Teas

I will be the first to disclose the I know nothing about the proper and formal tasting of pu-erh tea. I will share my experience and impression of a few teas. This should not be considered a technical evaluation or review.

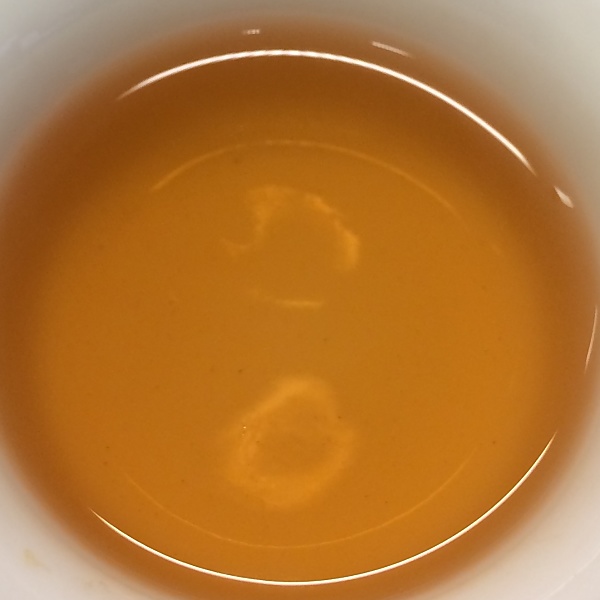

Raw

This is a 1999 CNNP (Zhong-Cha) Green Label, acquired from Upton Tea Imports. This is a raw cake “from an ancient tea forest.” Initial steepings showed mild flavor with a hint of nutty sweetness and faint drying tannins. The finish has a mild bitterness. The cup has faint aromas of earth and flowers, with some vegetal characteristics still present. Later steepings had more sweetness, a little smoke character, and a wood/loam element. There is a juniper finish that starts developing in the fifth steeping and beyond. The steeped tea is ochre and retains incredible depth of color through repeated steepings. The finish lasts several minutes. Quite lovely.

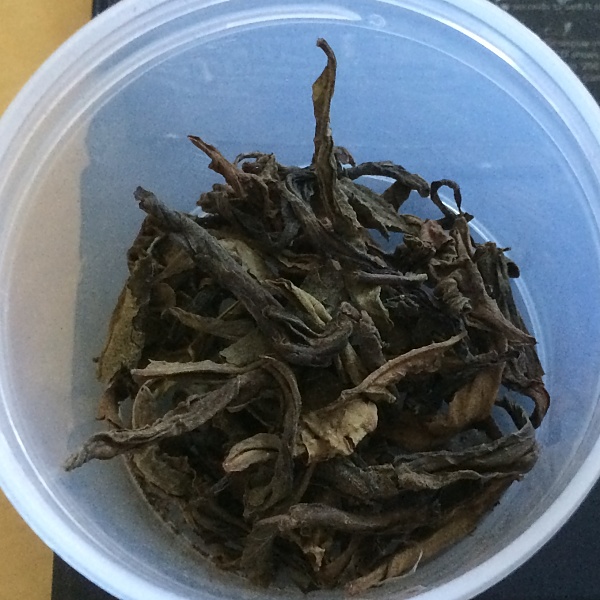

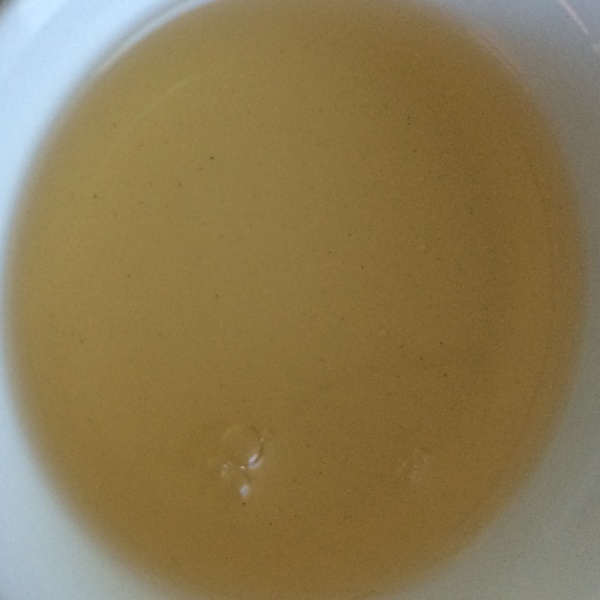

I know even less about this China Ancient Forest Green Pu-Erh, beyond that it is a single batch production from 1995. I acquired it from Upton Tea Imports back in early 2012. This is a loose production instead of a compressed cake, and the leaves are a lovely brown with a hint of green. Not bad for a raw pu-erh almost two decades old! To think that this is still a baby with another 15-20 years to go before it starts peaking (loose raw pu-erh has more exposed surface area and thus ages more quickly). The stepped tea is golden in color and not very aromatic. On the palate it is very smooth, with a sweet and long finish. Floral mid-palate and finish. Incredibly clean. Rich and buttery mouthfeel. Wonderful. Going to be hard to let this age appropriately.

The 2007 Youle Ancient Tree Pu-Erh is a young green pu-erh. I acquired this in sample quantity from PuerhShop.com. The samples provide enough tea for several sessions and are expertly removed from the cakes, which make them a fantastic bargain for exploration. The steeped tea is lightly copper-colored. Flavors are mellow, good mouthfeel. Definitely still has some green characteristics on the palate, along with more astringency and bitterness than the previous examples. Reminiscent of damp popcorn (pleasantly, to be sure). Not unpleasant in repeated steepings, but more of the astringency and bitterness comes out. Presumably “this will be better in years to come” if everything works as described.

Ripe

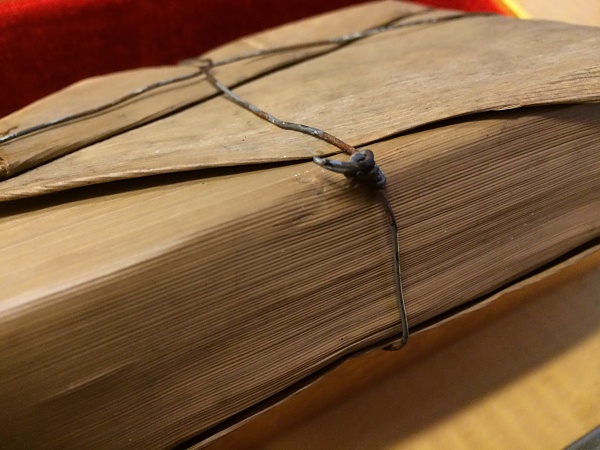

The next tea is from the early 1990s (exact year unknown). The Shi Zi Lauo Cha is a ripe tea from Menghai Mountain. This was acquired from Ku Cha. The tea comes packed in bamboo leaves held in place by an iron wire. The tea has more forest floor and earthy (well, let’s just call it decomposition byproduct) aromas and flavors, and is far more bold than any of the raw styles. Still, with some age this tea shows decent integration and balance. The finish is fruity with some berry notes, of all things, and the steeped tea is brown with a tinge of red. A little bit of musty aroma is present, but it does not overpower the cup. The tea is not at all astringent, but it makes my throat feel dry. Not bad, but I can’t say as it’s particularly special versus any recent-vintage ripe I’ve had. Subsequent steepings provide better mouthfeel, more of a red extraction, and more notes of earth and mushroom.

The 2004 Old Youle Ripe Pu-erh Tea Brick is another sample from PuerhShop.com. Like the previous sample, this is also from the Youle/Jinuo Mountain. Unlike the previous, this is a ripe cake and a different vintage. Brown with a pronounced red hue. A lot of color intensity that holds up under repeated steepings. Quite smooth. Rich and creamy mouthfeel. Earthy aromas are present. The finish shows dusty tannins. Not much sweetness in initial steepings, but this develops more with each pot. While lacking in some of the complexity (especially in the finish), this is the closest I’ve seen in a young ripe pu-erh to approximating the characteristics of a 20+-year raw brick.

The final tea I’m going to talk about today is the 2004 Zhong-Cha Yellow Seal, acquired from Ku Cha. This is a ripe 2004 cake, an interesting contrast to the 1999 Green Label. The tea is a vibrant garnet, though the pictures do it little justice (true with most of these). There is a distinct plum-like flavor up front in this one. Earthy aromas are met by a smooth mouthfeel and a delicate and sweet finish. Color intensity here is also quite pronounced and holds up for numerous steepings. This tea really develops a great integration between the sweetness and earthy components in the later steepings.

Closing Thoughts

For the money, the ripe teas are hard to beat. They may be crude approximations of aged raw teas, but remain quite enjoyable. Young raw teas are not intensely satisfying to my palate, and aged raw teas quickly become exorbitant. A great ripe pu-erh can be had for far less than a dollar a serving. A great raw pu-erh with decent age on it will run many dollars per serving.